Translation Notes: Lessons on Praxis from the Translation Lab, Part Two

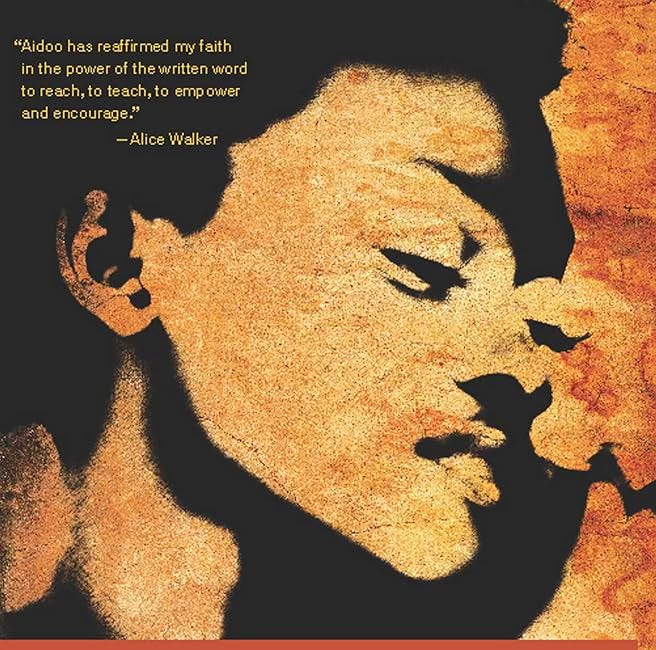

This two-part series offers an in-depth look at The Translation Lab’s approach to translating Chapter 14 of Ama Ata Aidoo’s Changes: A Love Story (1991).

The Translation Lab read and slowly translated Chapter 14 of Ama Ata Aidoo’s Changes: A Love Story over the Spring 2025 semester. Changes, set in 1980s Accra, Ghana, follows the story of Esi, a young, professional woman navigating the tensions between societal expectations and personal ambitions. Over many conversations about the text, TL ruminated on the cultural specificities of language, the differences in translating genres, and the richness of linguistic expressions. Individually and communally, they engaged and wrestled with the text, sometimes painfully, sometimes humorously, and always enthusiastically.

Read part one here:

Translation Notes: Lessons on Praxis from the Translation Lab, Part One

The Translation Lab enacts diasporic solidarities and witnessing through a translation practice rooted in Afro-feminist ethics, African intellectual traditions and knowledge ways, and decoloniality. The Translation Lab is part of the Community Knowledge Lab in

The following conversation unfolds among members Awa Diagne Lô, Chinese Calhoun and Afua Baafi Quarshie, who held space for the exchange in St. Louis (Senegal), New Orleans, and Minneapolis, respectively. In Part One, they discussed the first of three lessons they’ve gathered along the way. Now, they explore joyful synergies and the cultural specificities of emotion.

Welcome unexpected joyful synergies: While translating across cultures can be challenging and introduce us to the unique aspects of a culture, sometimes, as Awa found in translating the quote below, you encounter unexpected similarities and synergies between cultures that spark joyful connection.

“When her grandmother was all dressed in her starched cloth that made the most intriguing noises when she walked, she came to ask her, ‘Please let us sit down, my lady.’”

Awa: There’s a little segment. I mean, this first one was like in terms of accuracy, I wasn't getting to the meaning, but there were some things I had fun translating into Wolof, like one of them was the starch cloth, because Wolof has a term for it. So I was laughing when I saw it. We have a term for it. Yeah, we say it. We say yere yu ñu gome: clothes that are starched. And I asked my mom what sound it makes. My mom said it's the kàdd kàddaaral. We put the product in the batik cloth. In Senegal, people wear a bazin (batik cloth). You cannot worship without putting it on during Eid and other celebrations. You see, when the men wear it, it's almost like it's a structure by itself. And it gives the clothes' shape. It doesn't just drape, it has structure. So yeah, you need it. And if you wash it without starching it, it looks bad. Yeah, for sure we have the expression. Same for the sentence, “Esi’s heart sank,” that’s also perfect in Wolof. We have an expression for your heart sinking. You would say xòl bu ne rës. If we say, jom, it means to have courage. So it's like your courage is down on the floor. It was really nice, guys. I had fun. It was really cool translating those parts.

The language of emotion can be very culturally specific: How many words and meanings exist in different cultures for specific emotions? In the exchange below, we discovered the many ways one can express hate, love, and attraction in Wolof, Twi, and Swahili. The English text is deceptively simple: “So exactly what was it about Oko that repelled her so much, and what was it about Ali that attracted her?” A straightforward question in English ignited the rich conversation below.

Awa: The other word I had questions about was the choice for repel. “Repelled her so much.” I thought, 'How am I going to translate" repelled "?' That's such a strong English word. I didn't want to do anything with the person, but I felt I was cheapening it if I said 'bañ.' Because bañ is closer to hate. In Wolof Bani is to hate. It also means to refuse something. But I felt that wasn't enough to cover what was said here, you know? So curious about you approached it?

Afua: So, for me, the word that immediately came to mind is this word, nyan. It's an expression of like, ni ho yɛ mi nyan. And it's like, I'm disgusted by this. Like, it's not necessarily hate. Something about this person, just … it's almost … actually, the word nyan, literally translated, means it smells bad. Like food that has gone bad.

Awa: Wow. Yeah, that's some hate right there.

Chenise: Literally, they repel, like, it's like making you want to move away from it.

Afua: Move away from. Right? Because she uses repulsion and attraction, right? Which in English are actual opposites. If you're thinking about the magnetic. And it's physical in a certain way, but it's also like: eew nipa wei ho y3 mi nyan, so there's nothing about this person I like.

Awa: So Wolof is weirdly precise in some cases. And this is one of those cases, because depending on the brand or level of hate, it will think. So again, I think I will not use the word “bañ”, but another one that is even stronger. If you say, for example, this, this makes me feel outraged. You would say “lif, dafay buddi sama xol”, like it uproots my heart. Basically ... But still, I feel like this is not like 100% fit in the meaning, the way I feel in English. Yes, it's a profound disgust, but I'm not finding it in Wolof. I don't know why.

Afua: Because I think that she uses hate later on in the text, right? Like when she talks about how the sisters and the mother and whoever feel about her, they hate her, right? It's different. So she uses repel, then hate. And so the reason why I went with it is that the repel gives it a physical connotation. Because then we move into attraction for Ali, which again is like I'm attracted to Ali, not so much to Oko, because, ew, you know?

Awa: Yeah, that part will be really hard to grasp. I mean what I had before, when I mentioned it today; I said something like “Lan moo ko mèttiwoon,” if you remember. Like “Lan moo ko mèttiwoon dëgëntaan”? Uh, what was truly hurting her? And because in my culture, when you ask somebody like, let's say I'm sitting moping and I'm sad, somebody will ask me “Lan moo la mètti” ‘what is hurting? What is hurting in you? And it's not necessarily a physical hurt. Basically, what's wrong? And then, if I say it's “Lan moo ko mèttiwoon dëgëntaan” “tell me, like for real, what is exactly the problem now?” So you're getting at the essence of it. So that's what I did, because I try not to look too much at the English and just naturally visualize myself in a situation where I would say, but yeah, I don't know. Yeah, that physical aspect would be hard for me to put in Wolof for sure. Yeah, that's brilliant. English allows you to do it here really well with the double meaning.

Afua: And I think if you factor in the fact of the rape, it makes it even more so. Because it’s his final sin, it wasn't his only sin. But his final one was raping her. It was very physical, as if he was saying, you think you have a better job, you think you do all these things. But physically, I'm a man and I'm stronger than you. I can overpower you, and I can do what I want.

Awa: And maybe something else that would work in Wolof would be “soof”, because, do you know, Chenise, you remember. It means “annoying.” If I say soof’, it's like you're annoying. But it has another figurative meaning, for if you're eating a meal and you start feeling disgusted, you know that feeling where you're like, ‘oh, I can't eat it anymore?’ That's the “soof” feeling. So, if you say a person is like that, it can mean either that the person is annoying or that you're done with this person.

Afua: Oh, I think that's the one. Yeah. That's the one.

Awa: I'm going to tell my mom and see if she's going to catch both meanings.

Afua: Chenise, what did you use?

Chenise: Because the word repel, like, I mean, yeah, I know it's English, but it's the. If we're thinking that this is a conversation, then it would be the grandma who asked it and not Esi. I don't have a word for repel. I skipped over it. I have a word for 'attract,' but the word for 'attract' is actually the word for 'interested,' kuvutiwa na. To be interested in. What made you so interested in him? So I was thinking, what's the opposite of that? And so I was thinking, maybe I can use the verb for what bores you so much about him, or what makes you tired, kukuchosa. I think that would work. But I just feel like in the context of the book, maybe those words don't work the best, but I'm thinking in terms of, what's the best opposite for attract? I'm not entirely sure what I would put. It's just empty.

Awa: It's funny you chose that, because the word I chose in Wolof is loaded. Definitely. Like I use the hemmeem. Which is used only when you're infatuated with the person. That's what also distinguishes it, just like Arabic, it has a very specific word for being in love with a person, being infatuated with a person, or simply liking a person. So those are three different words in Wolof. I'm not sure. But I wasn't sure if that was also appropriate.

Afua: I think so, because I think up until this point, they're not taking her interest in Ali seriously. It's like they're genuinely baffled. Like, what is this thing? That's interesting, because now I'm going to reconsider what I used for the attraction.

Awa: What did you have for that word?

Afua: I was not sure what word to use. So I used a phrase: dɛn na ɛsɔ w’ani wɔ ni ho? Like, what is it about this guy that makes you happy, like, satisfies something in you?

Awa: We all three went in different directions. We had, like, a different flavor.

Afua: I like the slow translation.

The Translation Lab enacts diasporic solidarities and witnessing through a translation practice rooted in Afro-feminist ethics, African intellectual traditions and knowledge ways, and decoloniality. The Translation Lab is housed in the Community Knowledge Lab in The Diaspora Solidarities Lab (DSL).

The Diaspora Solidarities Lab is part of the LifexCode ecosystem.