Dignity, Remembrance, and Closure.

Meet Dr. Eva Semien Baham, retired professor of history, who led the fight in researching and recovering Black ancestral remains from Germany.

Please introduce yourself. How do you define yourself professionally?

I am Eva Semien Baham. In the south, particularly in South Louisiana, when you're from somewhere, that's where you are born and reared, so I'm from Southwest Louisiana. Where I live now in Southeast Louisiana - I live in Slidell, Louisiana. I work most of the time in New Orleans.

[Southwest Louisiana] has a very rich culture. Many of the people that you hear about in Louisiana still speak French, or what has come to be known as kouri vini. That's a Creole language. It's a complicated meaning. So if you translate it, it's something like, come here and go there, something like “courier,” you know, run. So it is a true Creole language indigenous to South Louisiana. It was the language that my father spoke, and my elder sisters and brothers. I don't have a hint of it, mostly because of what happened from the 1920s on [when] the state of Louisiana forbade the teaching or the use of French or any variations of any Francophone languages in Louisiana, as they were trying to anglicize to bring in industry. So by the time I came along in the 60s, [most] people did not speak it to their children. It was wiped out of the schools. And as you may know, when you take away language, you take away a lot of the culture, [but it didn’t] get rid of the culture here, because people kept talking and speaking the Creole languages here in South Louisiana, outside of business. Many of the people that I have had contact with in my own culture here have sympathies with particularly Hispanic people who are told to speak English, speak English, because that was done here to French speaking people in Louisiana. And if children went to school and had not heard English spoken, they would be treated very badly. So that, you know, is something that could have a detrimental effect on culture.

My undergraduate [degree] is from Southern University, and I had the wonderful opportunity to spend a year at UC Berkeley, and my degree was in journalism. I graduated in 74, so yeah, I'm way back from college, and I made a mistake, if you will, and when you look back on it sounds like a mistake. I did not take a fellowship to go to graduate school because the boy was just too cute. We married, and then had a family. And so 10 years after undergrad, I went to graduate school, and I went to Purdue University. My emphasis in graduate school was American Studies and History.

After graduate school, I came back here and was hired at Southern in ‘91 to teach there, and I taught there for 20 years. And then my second stint was here at Dillard in New Orleans and so and I retired from Dillard two years ago so that I could do all those projects that I've been trying to do all along, and so on. If you're an academic, you just love learning, so how do you stop learning?

I would love to hear how you make sense of your background as a journalist and how that plays into being a historian and a genealogist.

I like to explain that having that interdisciplinary coursework in American Studies with the focus and emphasis on history informed my teaching in history, because I almost always take an interdisciplinary approach … There is no one way, so I have students study all aspects of something happening in history. I think I couldn't think of teaching any other way. My own work has been what I like to call some form of eclecticism, because I have just gone in so many different directions in the work. I wasn't always able to publish work, but I was always able to bring it back to the classroom.

I have argued that, in a recent publication, that history and genealogy are traveling companions, and that we need to understand both because I belong to a genealogical group called the Louisiana Creole Research Association, and these people have done extensive research in the 20 years of that organization and, prior to the formal organization of the association, they have done extensive, extensive research on their backgrounds. When combining history and genealogy, I want to know what was the context of the existence of people at a certain time? Of the people that I'm researching, in what environment were they living and how did that form who they were and their succeeding generations? For example, I have researched my family, back to my great one side, my great great grandmother. Oral histories [and conversations] need to be taken very seriously, because the story that came from her in the mid-1800s to her daughter, you know, to her daughter, on and on, and to my mother that had a daughter who was sold and taken away at about 12 or 13 years old. I try not to get too emotional about it … they told it with the same kind of pain that the great-great grandmother felt when her daughter was being taken away. The story comes down that she's running behind the wagon. She's screaming, “Don’t take this child.” Well, we can visualize that, and we understand how children were taken away from their families.

In addition, [the daughter] was the child of this great grandmother and the slave owner. She was apparently fair and she wanted somebody that looked like her, who was going to take care of her. So, gee, that sounds like the whole concept of fancy girls! So, yes, genealogy and history work together for me, and I can't tell one story without the other and certain people.

Regarding genealogy and at the very beginning, you had mentioned different forms of erasure, but specifically in taking away people's language. And I love that you mentioned it. Are Spanish speaking people, because I myself have a mother's side of the family that’s from the island of Puerto Rico, and younger generations are often made fun of because we generally aren’t fluent in Spanish. We being the second and third generations of Puerto Ricans.

And what I'm curious about, the connection in that research, not only in your research of genealogy, but the connection from your childhood and growing up in that region and then seeing the importance and the devastation of erasing or trying to attempting to erase that culture and like what it means to the people who you're connected with, it’s something I'm very curious about in the context of when you first started digging in?

Well, this is the irony: in the latter part of the 20th century, here in South Louisiana, a movement began to bring the language back, particularly the French and Francophone languages. An organization came out called CODOFIL. CODOFIL is an acronym for Council for the Development of French in Louisiana. So from the 1920s on through the 70s, maybe early 80s, it was like, “Oh, you have to speak English.” I don't even have a hint of an accent, because it was encouraged that if you wanted your children to do well, then they had to speak English well, so they were trying not to speak it in front of us. So when CODOFIL came along, that was the irony of it. [They went from] trying to erase it to importing French teachers from French-speaking countries, particularly here to come, to teach children French in elementary schools. It also extended itself to Spanish, because they brought in Spanish-speaking teachers to Louisiana to teach Spanish in elementary schools, to try to get back what was lost in our schools. In many places, the elders continue to speak the Creole languages as well.

What is your role with LifexCode?

I am part of the Community Circle group of Keywords for Black Louisiana, and I help bring people on board. One of the other roles that I take is, along with Dr. Wendy Gaudin of Xavier, we have scouted out additional places in Southwest Louisiana, in the Opelousas, or St. Landry parish courthouse, and it's like a gold mine. And Opelousas, of course, is one of the early settlements by the French there. We have also gone to St. Martin parish that's in that same region in Southwest Louisiana to look at some of their documents in French. Like you know, people come to New Orleans, where it is just a gold mine itself of French and Spanish documents, but in Southwest Louisiana, you also have them there. [That region] held on to their Francophone language, or has held on to it longer and more tightly than here in the city. So you'll see that there are documents [when] you go to University of Louisiana: Lafayette, and there are documents in French, there are documents in Spanish. [So] we're looking at places for this summer that will create an opportunity to see where else these kinds of documents are.

We also wanted to ask about your recent leadership of the Dillard Cultural Repatriation Committee. For readers who don’t know: a Dr. Henry Schmidt of New Orleans gave 19 crania to a Dr. Emil Ludwig Schmidt. These skulls belong to the bodies of Black people who had been treated at the Charity Hospital who died in 1871 and 72. Their bodies were decapitated. Was it by Henry Schmidt? Do we know?

I'm trying to encourage other people to take on additional research, to do this, to do further research into this, to look into those charity hospital records, which are voluminous, to see if they can find out more details about it. I want to make note that charity hospital was, until its closing after Katrina, a teaching hospital.

And so we know that potential doctors are trained on cadavers, so I am assuming that they use bodies to train doctors. [There was] no refrigeration, so much of the training that was done [on these bodies] was done in the winter.

What we do know is that there were 19 individuals there. We try to talk about them as people and individuals. Ms. Freddie Evans and I were charged with the research. We went to the public library to search the Charity Hospital Death Records - that's exactly what it's called. We had three anthropologists, one archaeologist, and so Professor Christine Holland (an anthropologist on the team) was the first person to tell us, well, “Maybe you could find something in the desk records there in the public library.” So that's where we went … And it just appeared these people died from a number of things. There is no suggestion from us at this point that they were killed for this purpose.

We were going through all these records, and we had all their names, approximate ages. [At first] we did not have a date of death. But guess what? We came upon one of them, and then another, and then another. They all died within days of each other, wow, in December 1871 and then early January 1872 and we do have a document, a letter between the Schmidts that said, ”I'm sending the skulls as I promised.”

Do you know how the doctors knew each other?

I don't, but it seems that they had a relationship. Schmidt in New Orleans was from Germany. He came into Pennsylvania, I think Philadelphia, then, I think [he moved] somewhere in Alabama, maybe Mobile, and then made his way to New Orleans. He was supposed to have some expertise in phrenology. We didn't get the sense that he was a doctor when he came here. [In the] 1800s US, you could go to medical school and become a doctor in a short time. It was much more advanced in Europe.

[Looking at a catalog written by Dr. Emil Schmidt] Here he says, “I owe gifts to Doctor H. Smith in New Orleans.” And he numbered them 790 through 808, so in the catalog that they have [in which they recorded these people] and the catalog, they're numbered 790-808. It comes from Emil Schmidt's “Catalog of the Craniological Collection Displayed in the Institute of Anatomy of the University of Leipzig. According to the stock of 1 April 1886 compiled by Dr Emil Schmidt.” And there's another notation: “Compiled in 1887.” I'm not sure at this point if they were sent in 1886 or prior to that.

[The catalog] described them by years old, and we know that's oftentimes approximate. So for example, Professor Christine Holland went to Leipzig and reviewed the catalog and reviewed the crania to make sure that what they're telling us is there [about the crania] matches what the anthropologist has examined. For example, there's a woman Alice Brown, who's listed here as 15, and [Professor Holland] examined the dentition of the teeth, and she said that in her professional view, that person was more like 20 20-something. She examined another person, a male, John Tolman, and in the catalog, they had him as 23, but she said her examination shows that he was probably something like 30 or 40. She went to Leipzig and she was able to see them. When we look at the Charity Hospital Death Records, we see [something else]. So the catalog says that Alice Brown was 15, but the Charity Hospital Death Records matches what Professor Holland said - that she was 43.

We do know that the city archaeologist, Michael Godzinski, as well as the anthropologists who worked very closely with us finding a space for the Katrina memorial gravesite, told us that many of the Charity Hospital dead were buried where the Katrina memorial [is]. This is going west if you leave Canal street, away from the river, and they believe that there are bodies buried underneath the streetcar line there. This is about where they think that those bodies were buried. This is the reason why we petitioned the Katrina Memorial gravesite to bury them there.

And we had to have a lot of conversations with them about it, because it was for Katrina, you know, the dead and Katrina, and so we had lots of conversations about it, to say, “Could we put them there? Listen, it's, it's nothing scientific in our sense, that we could say that they are there, we don't know, but it's possible, because that would have been on the edge of the city, okay,” and we are saying, “Well, at least we could put their crania there.” And we could just believe - it's like reuniting in the abstract.

Why did the doctors value the skulls?

This whole [area of] study, which is called a pseudoscience, phrenology, was meant to determine through only the skull, a person's personality and character. So personality has to do with behavior, right? And character has to do with your morals and ethics. So how do you determine those kinds of things, just through the skull? They would use something like bumps on the head or certain things from the skull. You can see why it's called a pseudoscience - it's just fake because you don't know [if] somebody was hit on the head. Even in the transport and in the decapitation process, what happened? They used their findings to determine if people are inferior or not. One of the conclusions that I've drawn from this is that these people started off with a conclusion. In science, you start off with a hypothesis, a guess, right? You want to prove that one way or the other. With phrenology, their efforts were to substantiate what they believed already.

Was it common for doctors to send crania to each other internationally?

The professor and doctor from Leipzig told us that Indigenous people from New Zealand [recently] went to Leipzig to take back the remains of their dead. This was done by people all over the world. Numerous countries in Africa, places in Africa. And while we were doing this, I think, last fall, [it was] documented in the New Orleans paper that the remains of an Indigenous community were brought back to the United States [from Leipzig]. And then Dr. Garica told us that there are 600 more cases, not 600 more crania, but cases around the world. I also saw, in the New York Times, after an interview I did with them, that this was perhaps the first repatriation of African-Americans from Europe.

I saw that as well. I wanted to ask you if you had any thoughts on why this one actually happened when so many others haven't.

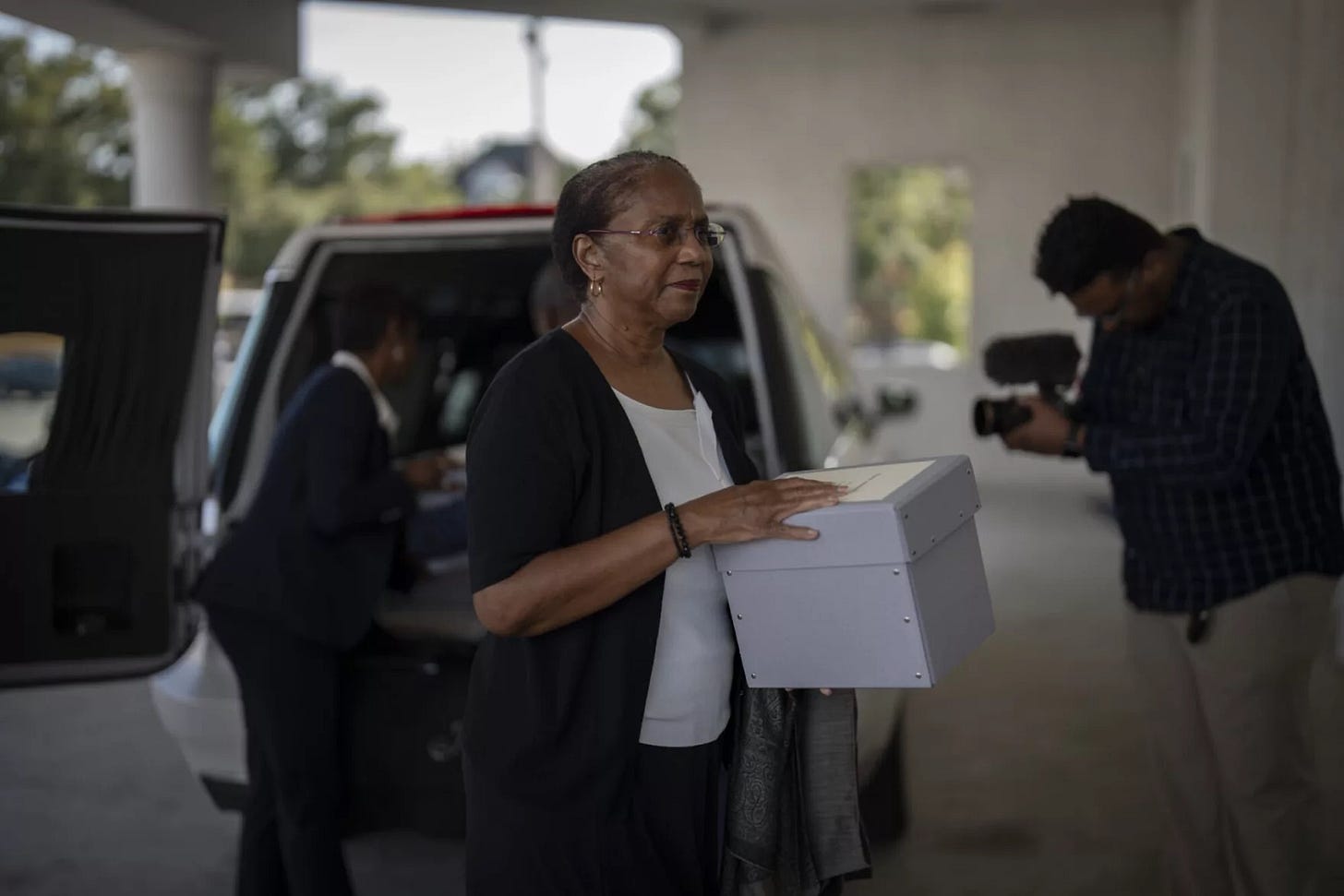

Because of the collaboration of the people working on it. Leipzig contacted the city of New Orleans in May 2023, and the first person they contacted, or this was brought to the attention of, was Michael Godzinski, who is the city archaeologist. He contacted two other people who worked at the Department of Justice in Louisiana, Dr. Ryan Seiderman and Professor Christine Holland. And they also spoke with Dr. Ryan Gray (professor of anthropology from University of New Orleans). [Dr. Gray] contacted me in April 2024 and asked me to organize people. We [now] call ourselves [the] Cultural Repatriation Committee [with the goal of being] in line with the ethics and standards of the American Anthropological Association … on this specific topic of how to treat the remains of people and how to repatriate them. [One of our main goals was that] they must be repatriated culturally appropriately. They should be brought back to their communities according to the cultural standards of that community.

Dr. Baham discusses the interfaith memorial:

A year ago, we organized with some of the people in New Orleans who, among New Orleanians, especially black New Orleans, [are] called Culture Bearers. It's actually a title given to people - or they might take on themselves - who sustained them, unapologetically sustained the culture. We [also] brought in the Black Men of Labor [who] oftentimes you will see with the jazz band. We brought in Dr. Michael White, who is a noted jazz musician around the world, and his band. They came in under the guidance, if you will, of Mr. Fred Johnson, who is a founder of the Black Men of Labor, who are the people you see oftentimes doing jazz funerals. They explained to us in great detail what must happen in a jazz funeral, as opposed to what happens as it has been translated through time in younger generations. We wanted something rooted, so they researched jazz funerals in the 1800s. We also wanted to bring in almost as many of the spiritual elements that are indigenous to New Orleans as possible, so we had an interfaith service. It represented all of the different cultures that are in New Orleans. One person said to us, “Oh, this is so New Orleanian. Only in New Orleans [could you] do it the way New Orleanians do it. [We brought in] an organic culture in New Orleans. It was not a performance. It was all very real and very spiritual and indicative of what it means to bury the dead, particularly in Black New Orleans culture.

We would love to hear a little bit more about what this committee and the repatriation means to you.

This repatriation has been quite a moving experience for me and for the committee. I want to make sure that they all are part of this conversation: Dr. Jana Smith from Dillard University; Dr. Clyde Robertson, African American Studies at Southern University; Mr. Fred Johnson, who is co-founder of Black Men of Labor; Mr. Leon Waters, who is founder of the Louisiana African-American Museum; and Ms. Freddi Evans, who is noted here in the city. She just finished a book on John Scott, the sculptor. In addition to them, the people from the Black community who understood Black New Orleans, New Orleans culture, and its roots, and what is real about it. They would come in and say, Well, we need this part of it. We need the Congo Square Preservation Society. We need the drummers. And also, we need the people who did something called AJaJa in the ceremony. And Michael Godzinski, the archaeologist; Dr. Christine Hollins, Dr. Ryan Seidemann, and Dr. Ryan Gray, who were the anthropologists; and the president of Dillard [Dr. Monique Guillory], who said, “This is what our HBCU should be doing.” We met in her boardroom. She opened up all Dillard’s resources and said, “Let's work on this together,” so she was there every step of the way. I should not leave out the Mayor of New Orleans [LaToya Cantrell], who, without whose support, her staff, her team, [the repatriation] would have died two years ago in conversation. So she, too, was important in this. And what all of that means to me is that a collaboration of all those different forces in New Orleans, what makes South Louisiana, what makes New Orleans culture, is rooted in that African descendant culture. I am so deeply and profoundly moved by this, the impact of having all of these facets of New Orleans culture that's organic. It is non-performative. It is real.

From the committee meetings very early on, [committee members] were all just stunned by what happened to these people. They died of different maladies, and then their bodies were thrown away, and then they were decapitated, and what happened to them - I need to say: it served as some of the roots of what would happen to Jewish people in the Holocaust. A lot of these studies were used to justify the inferiority of Jewish people and people around the world.

Mr. Fred Johnson was adamant about this first, and everybody else amen’d it: “We are going to insist on this. If what we are doing is only going to bring their crania back here and be put in a vault, we're not doing it.” Because, as Mr. Johnson said, we will have committed the same crime to these people. And he said, “I'm not going to be a part of it.” Over and over, people in our community meeting that day said they made a pledge that they did not want to bring them here and be put in the vault. They had to have a service. They had to have a proper New Orleans burial or nothing. And that was agreed upon in our group. We decided that we would not discuss this with people outside of that committee. We worked so well together. And I keep saying we, because it's about all of us. We worked so well together that they did not and, and Dr. Jana Smith said, We are not going to tell them to make this public until they have landed in New Orleans, and that's when we made it public.

The LifexCode team extends profound gratitude to Dr. Eva Semien Baham for taking the time to sit and discuss her magnificent life and crucial work with us. Thank you so much for reflecting on this journey with us. May we never forget.

Learn more about the 19 individuals returned to New Orleans and view the memorial and jazz funeral on Dillard University’s website.

The 19 individuals were: Henry Allen, Henry Anderson, Isaak Bell, Alice Brown, John Brown, Adam Grant, Prescilla Hatchet, Mahala, Hiram Malone, Marie Louise, William Pierson, Samuel Prince, William Roberts, Hiram Smith, John Tolman, Henry Williams, Moses Willis, and two who remain unidentified.

Short biographies of each individual are also available from Dillard University at this link.

Dr. Eva Baham is a member of the Community Ethics and Engagement team for Keywords for Black Louisiana.